The first chapter of this work was centered around defining the fundamental category of human existence — the ethnic group, and things that were inherent and proper to the ethnic group. As hinted in the first chapter, there is a distinction between the ethnic group and the nation. The ethnic group evolves into a nation through a process of self-identification, though nations are fundamentally ethnic groups. In this chapter, we will primarily be synthesizing the works of Dr. Connor as well as Fr. Adrian Hastings in how nations are born. While every nation has its own history and process in its birth as a nation, we can broadly categorize the nationhood process into three stages.

The first stage is that of pre-nationhood. This is when an ethnic group is other-defined rather than self-defined, when the ethnic group roots its identity in something other than the ethnic identity. In this state, there is a mass of unstable, local communities of the ethnic group. This is also the stage in which an ethnogenesis can take place. Throughout this chapter, we will be looking at the English as a case study as, in many ways, England is the baseline example of a nation. Fr. Adrian goes so far as to suggest that one could conceptualize England as the "first nation" from which the nation model emerged. I certainly agree that England played a major role in the nationhood process for many nations — in many ways, it worked as the first domino in a chain for others. But note that there were nations before England.

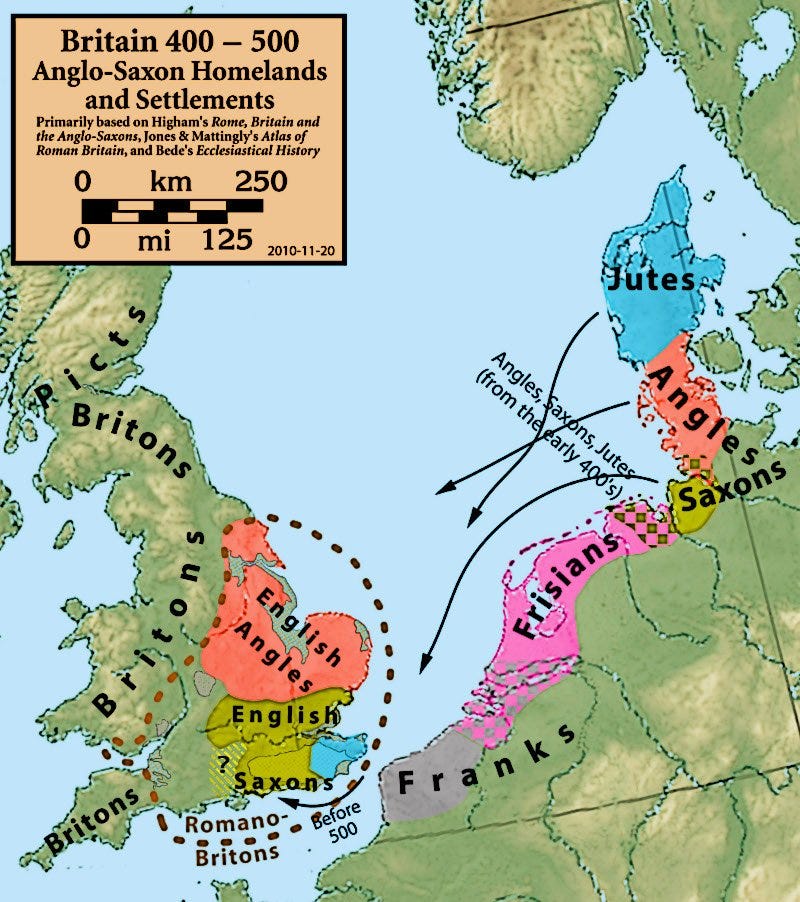

So what was England like in its first stage? In the first stage of nationhood, we could look at Britain in the 6th-8th centuries in which Scots, Picts, Celtic Britons, and incoming Angles, Saxons, and Jutes inhabited the island. Particularly focusing on the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes, these Germanic peoples held their identity in their tribes and though they recognized as shared heritage with others in their group, their identity was rooted in the tribe or clan or fealty to their king.

Gradually, the ethnic group will enter into the second stage of nationhood. It is hard to apply any set criteria for when this stage is reached, but there are many indicators for this stage. For one, the ethnic group will see the development of one or two literary languages (A vernacular language shared by the literati of the ethnic group rather than the oral languages which can see strong regional variety). Gradually, tribal affiliations merge through alliance or conquest and larger states are formed, diminishing the complexity and fluidity of the map. As a rule, anywhere there is something identified in history as a "dynasty" suggests the existence of some sort of nation as a king is usually identified as a leader of a kin. Mutli-ethnic empires are also usually dominated by one nation at its core (consider the domination of the early Roman Empire by the Latins/Italians).1

Let us take note on the value and role of a clerical class. In the case of western Europe, the clergy were the most responsible for fostering national identities in local communities from the 13th century onwards. They were responsible for translations of texts which creates and stabilizes a vernacular language. The clergy formed stable communities at the local level and provided connections to national universities in bigger cities in early nations. The clergy also mediated between the common folk and the king, developing this vertical relationship. The clergy, indeed the organized religion as a whole, plays a major role in the formation of nations particularly in the second stage.

In that vein, let us make a note on associating religious identity with national identity. Whenever a people feels threatened in its distinct existence by the advance of a power committed to another religion, the political conflict is likely to have superimposed upon it a sense of religious conflict, similar to a crusade. Thus, a national identity can become fused with a religious identity. Scott Mannion mentions that all ethnic groups, all nations, are forged by the spiritual conquest of territory by people in the name of a god (our geist, if you will). The military exists to protect this land and the political and religious hierarchies were one and the same, later splitting for convenience. Religion and spirituality, loyalty to a geist is key in nation formation.

"Mythological" events that are key to the nation's identity often have a religious character — the Gunpowder Plot, the Siege of Derry, the Battle of Kosovo, and Joan of Arc come to mind. Nations often see their countries as a holy land and themselves as a sort of holy people and this helps to coalesce into nationalism which we will define more exactly in section III of the third chapter.

Let us also take into account the idea of a nation entering Christendom, a unique apparatus in the metaphysics of nations. Fr. Adrian provides a strong outline for how a nation becomes a "Christian nation" and enters into Christendom historically. To enter Christendom as a Christian nation, a nation must have a Christian history constructed from the baptism of a king, onward through great deliverances, the Bible must meditated upon in the nation's own language and the nation's own church must be fully independent of any other and identified with the nation. Then and only then, according to Fr. Adrian, does that nation become a true Christian nation in Christendom. And I am inclined to agree with him in absence of strong counterarguments.

Another note on England as a catalyst of nation statehood.2 England was uniquely suited to be the first proper "nation state" and would export that model to the rest of the world. England can be said to be a nation before 1066 CE. The Shires of England were constructed to develop the reality and consciousness of a unified country as they were too small to be seriously separatist yet important enough to focus loyalty in an essentially horizontalist and healthy emulative way. England itself had clearly defined territory due to geography as well as ecclesial unity which stabilized the intellectual world of England through vernacular literature (for example, St. Bede's written history of the English people), the growth of an economy and effective royal bureaucracy. The Magna Carta enshrined a unified sense of national identity as it was read out in local shires as a yearly event (much like a national liturgical calendar, creating shared holidays across the space of England).

The Norman conquest did not wipe out English identity and English identity would soon be re-established among the ruling class. The English Renaissance is often seen as an expression of that national identity. The Normans gave the English nation state model an aggressiveness needed to produce counter-nationalism on the nations it came upon lest other nations would be integrated into England. As a result, English identity could be called expansionist, developing an empire and exporting the model of the nation state. Scotland and Ireland had to produce models of nation states to defend themselves from England (we will explore this in the Irish situation soon). The nation state model was successful and every time it came into contact with other groups, it fought and overran them unless they adopted their own model.

What do we mean by this? Let us shift focus from England to Ireland. Ireland had geographic unity, language, law, literature, a historic identity, orders, jurists, and monks. By the mid-eleventh century, Ireland and Wales were definitely nations and not merely ethnic groups. However, they were not yet one nation state.

By the 1600s CE, there were two nations in Ireland but only one nationalism. There were two English groups in Ireland, the Old English (Irish-Normans) and the New English (Anglo-Saxons), along with the Irish who did not desire a nation state. The Old English and New English had a desire for a nation state as a result of it coming from their English background.

The Old English maintained Roman Catholic identity and lived in the Pale (Dublin). Roman Catholic identity allowed them to unite with the Roman Catholic native Irish under Irish characteristics of the Irish nation in contrast to the New English who were Protestants. The Old English imported the nation state politics into the Irish nation, leading to the birth of an Irish nationalism and a desire for an Irish nation state in reaction and in contrast to the expanding English nation state.

The so-called "Herodotus of Ireland," Geoffrey Keating (himself an Old English Roman Catholic) used his continental church training to create an ordered history of Ireland, building up a sense of historic unity. Protestantism was seen as a threat to national identity and helped identify Roman Catholicism with Irish identity and strengthen the sense of difference between the Irish and English nations. In this way, the English nation state model spread and Ireland was forced to adopt the nation state model to survive.

By the 15th century, many nations in western Europe had reached the second stage of nationhood. Even if not in political (i.e. state) form, most of today's main nations existed as nations at this time. Let us now speak of the third and final stage in nationhood which begins in the late 18th century with the Enlightenment and what we will call the "Age of Nationalism." With the collapse of the French monarchy, there was a popular spread of nationalism as the source of state legitimacy.

The "Age of Nationalism" refers to the impact of the Enlightenment and its ideas on the innate ability for an ethnic group to become a nation. Modernists make the mistake of pointing at the Enlightenment as the beginning of nationalism or of national identity but Keith Woods argues that the Enlightenment idea (that is the right to rule a nation is vested in the nation's particular ethnically defined people) was present in the philosophy of the Middle Ages and the philosophical democratization and proliferation of ideas in the Enlightenment merely popularized the idea of political nationalism.

The Age of Nationalism and the Enlightenment/technological changes that propagated it has developed mankind's view of nationhood and cannot be reversed. Ethnogenesis, for example, is much different in a natural, pre-Enlightenment world than in the artificial, post-Enlightenment world. Just because the Angles and Saxons became one ethnic group over a long period of time does not mean immigrant groups from one nation can perfectly assimilate and become part of another nation in one decade. The Age of Nationalism and the proliferation of its ideas have significantly changed the human condition in this regard.

Because of communications technologies, ethnic groups and nations outside the West (which served as the epicenter for the Enlightenment) could see the third stage nationalism of Europe and thereby activate the third stage nationalism within themselves. Consider the Indians who saw the Irish fight for independence from the British and thought "why not us too?"

The Age of Nationalism also ensured that the process of becoming a nation cannot be reversed. A tribal people who become a nation but are then conquered will simply become a latent nation underneath the conquering nation in the modern day. Ethnic and nationalist riots in the United Kingdom in the 1970s and Balkan nationalism in the 1980s and 1990s show this to be the case.

The Habsburg Empire may be an exception to this, but the Habsburg Empire is often misrepresented as the norm in multi-ethnic empire case studies. More will be said on the Holy Roman Empire in chapter 4.

We will talk more about states in section II of chapter 3.